How the West Was Won (1962)

By 1962 Hollywood knew the jig was up.

Audiences, with expanding options of quality programming on television, would no longer automatically show up to the cinemas for whatever fare they had thrown together. Actors and directors were tired of being workhorses for the studios, told to go here and do that, and wanted the power to pick their own projects. Certain quintessentially American genres, notably the musical and the Western, were increasingly seen as creaky and worn out.

The Golden Age, for good and naught, was waning — and everyone knew it.

The reaction from Tinseltown, at least for awhile, was to deliver things TV couldn't: color pictures, big action spectacles, widescreen formats, stereo sound, 3-D imagery and so on. One of the big ideas was Cinerama, which stretched an extremely wide image across a huge curved screen, so the audience literally felt like the movie was wrapping around their field of vision.

To get some perspective, the aspect ratio of most films today is 1.85 to 1, width to height. Modern flatscreen TVs are 1.78, so when movies are played on them you only get a little bit of black bar at the top and bottom. (Rarer) widescreen movies are usually 2.35, so the bars are much bigger. Cinerama was 2.59, so when I watched the film on my set the film only occupied the middle third or so of the screen.

Only two major feature films were made using this process, which involved shooting with three separate 35mm cameras and then using a trio of projectors in the theater. "How the West Was Won" was a big success, the second highest-grossing film of that year, but it was too expensive to outfit more than a handful of theaters with the setup.

When shown as a single image on a flat screen, the three pieces tended to not match up well, with noticeable lines during bright scenes. Since most theaters didn't undertake the upgrade, this is how most audiences saw it. Despite its early success, Cinerama died a quick death.

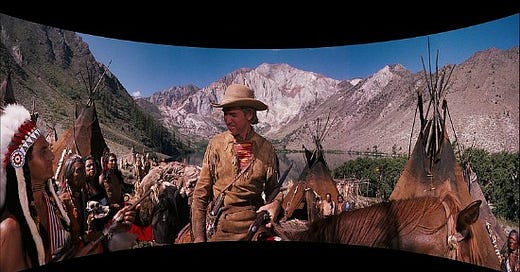

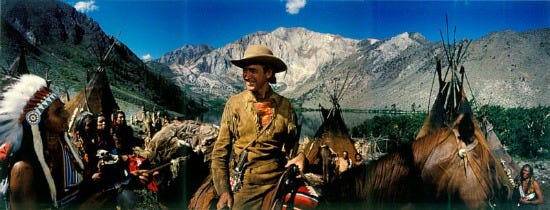

MGM undertook a restoration of the movie in 2000, and new Blu-ray editions include a version that simulates the curved Cinerama look. I've included two stills of the same scene above so you can see the marked difference in presentation.

Filmmakers didn't like the logistics of shooting in Cinerama, either, since it required them to position the actors and backgrounds in such a way that the performers might not even be looking at the person they were talking to in the scene. John Ford, who directed one of the film's five sequences, complained that you couldn't shoot closer than the waist up, which limited the ability to give audiences an emotional connection with the characters.

Much like the green screen technology of today, the final result could be fabulous, but required a talented and attentive cast and director to preserve the performance aspect.

The visual look of the restored "How the West Was Won" is often breathtaking, with glorious vistas of the American fields, rivers and mountains. Narratively the story spreads over 50 years, from 1839 to 1889, covering the settlement of Ohio, the gold rush, the Civil War, the building of a transcontinental railroad line and the height of the outlaw era. It's all told through the eyes of a single family, as subsequent generations grow up and move on further West.

The final movie was a languid 164 minutes, but includes lengthy musical overtures (by Alfred Newman) at the beginning, middle and end that probably consume at least 20 minutes on their own. Everything about the film telegraphs that it wants to be seen as an old-school epic, but really it's several small, barely interrelated stories strung together.

In a gimmicky move, different directors were hired for the five sections, though Henry Hathaway helmed most: the first, second and fifth. Ford directed the third and shortest section on the Civil War, which is really more of a vignette than a true standalone story. George Marshall oversaw the fourth and probably best sequence on the often merciless drive to connect the railroads from east to west.

It was nominated for a bunch of Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and won three for Sound, Editing and James R. Webb's screenplay — thought it did not get a nod, notably, for directing.

The film also has the prerequisite "All-Star Cast," though most of them have very fleeting parts. John Wayne is in it for about two minutes, along with Henry Morgan, playing great Union generals Sherman and Grant during the Civil War section. Jimmy Stewart has a bigger part as a frontier trapper who falls for one of the daughters (Carroll Baker) of cantankerous pioneer Zebulon Prescott (Karl Malden) in the first sequence. Stewart gets stabbed by some river pirates (led by the great Walter Brennan) but survives to win the girl.

Henry Fonda and Richard Widmark turn up in the railroad section as, respectively, a fiercely independent scout and the hard-case overseer of the building operation, who's willing to break the treaty with the Arapaho Indians and start a war if it'll mean shaving a few days off his schedule.

Gregory Peck plays a gambler who courts, then deserts, then nabs again one of the Prescott daughters, played by Debbie Reynolds, who wants to marry a rich husband and move back East but ends up as a saloon showgirl instead. Robert Preston plays the wagon train master who pitches his own woo at her, telling her about the matching suitability of his huge ranch and her ample child-bearing hips, but she's looking for a little more romance. Thelma Ritter plays an over-the-hill female pioneer who desperately wants to get married; I kept thinking she would hook up with the Preston character.

Eli Wallach turns up in the last sequence as Charlie Gant, a particularly nasty outlaw who avoided jail years ago and is back to torment the lawman who killed his brother. They each put lead into the other they still carry, so there's no love lost. It seems like a clear precursor to Wallach's Spaghetti Western roles later on.

Really the biggest star in the picture in terms of screen time is George Peppard playing Zeb Rawlings, the son of the Jimmy Stewart and Carroll Baker characters. He's the main character in the last three sequences. In the Civil War he's a scrappy young recruit who becomes disillusioned by the senseless killing. In the railroad section he's a U.S. Cavalry officer charged with keeping the peace, who continually butts heads with the Widmark villain. Finally he's the marshal, now with a wife and kids of his own, who faces off with Charlie Gant, as Debbie Reynolds returns as an aged doyenne of San Francisco who wants to spend her last years on a ranch.

Spencer Tracy narrates the tale with openings to each sequence, plus a flowery speech at the end about how the suffering and triumphs of those Western pioneers allowed us to have all the great stuff we have today. It's a little disconcerting as the airborne camera swoops over the vistas, which gradually become more and more occupied with the mark of humanity, including highways and smoke-belching factories. I suppose in 1962 those things were seen as hallmarks of progress rather than urban sprawl.

I guess I like the idea of "How the West Was Won" more than the totality of the movie itself. It's generally quite entertaining, and even grand at times. But it feels more like a lot of haphazard pieces washing down the current of history than a coherent film.