Miles Ahead

“Miles Ahead” is Don Cheadle’s riff on the life of Miles Davis, a master of improvisation, so it makes sense in many ways for him to treat the official biography of the jazz genius as a mere stepping-off point for his own concocted refrain.

But just as having masterful technical skills as an instrumentalist doesn’t necessarily mean you have the chops to make up music on the spot, the film’s dizzying attempts to inventively cogitate on Miles’ mythology sometimes wander off into narrative cul-de-sacs and side tracks that just don’t sing.

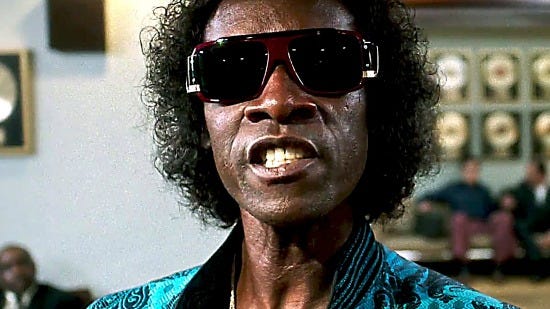

The esteemed actor gives perhaps the finest performance of his career, showing us the contemplation and calculation behind that ferocious mask of Eff You self-regard with which Davis obscured himself. We see and feel his hunger to create, the rage at anything that stood between him and his music, understand a bit of the towering pride that often harmonizes with talent.

Cheadle also directed and co-wrote the screenplay (with Steven Baigelman), his feature-film debut in both roles. It’s technically accomplished work; it hits a lot of emotional scenes solidly and certainly bespeaks of someone who has a future behind the camera if he wants one.

The movie mostly concentrates on Davis’ fallow period from 1975 to 1979, when he stopped publishing music and even ceased playing the trumpet at all, with flashbacks to his heyday in the 1950s and early ‘60s. The early biographical stuff more or less plays it straight, while the later scenes have the barest bridge to reality.

The latter involve a wild scenario in which Davis’ session tape, supposedly the chariot of his comeback, is stolen and re-stolen back and forth between himself and Harper Hamilton, a shyster agent played by Michael Stuhlbarg, complete with squealing car chases and blazing gun duels.

Acting as his wingman / witness is David Brill, a hipster Scottish journalist played by Ewan McGregor who was sent by Rolling Stone magazine to get the scoop on Davis’ return. Though Brill may be fudging about whether he was actually assigned the story, or just knocked on Davis’ door on spec. His initial attempts at an interview don’t go well.

Davis: “My story? I was born, I moved to New York, met some cats, made some music, did some dope, made some more music, then you came to my house.” Brill: “That's it? … I guess I'll fill in the blanks later.” Davis: “That's what all you writin' mother****ers do anyway.”

The movie is framed by a formal sit-down interview with the same journalist, apparently meeting for the first time, which is our cue that everything that comes between is mere rumination.

Cheadle gets deep inside Davis’ physicality, somehow bending a slight resemblance into near-doppelgänger accuracy. It starts with that sheathed voice, partly croak and partly purr, as if consciously trading volume for intensity. Then there’s the shuffling limp — the result of a congenital hip disorder in real life, but something else in the movie’s telling — and the deadpan snarl.

Cheadle even nails the straight-fingered way Davis bent his digits at the first knuckle perpendicular over the horn’s valves, instead of rounded like they teach you. As in everything, Davis played it his way.

Emayatzy Carinealdi is a vibrant presence as Frances, Miles’ first wife and muse, even appearing on the cover of his 1961 album, “Someday My Prince Will Come.” She was a rising dancer who gave up her career at his bequest, which sets off a downward spiral of resentment and, eventually, violence. The film regrettably short-shrifts Davis’ long history of domestic abuse.

Keith Stanfield, a young actor who’s been phenomenal in small films like “Dope” and “Short Term 12,” plays Junior, a fictionalized novice trumpeter who gets unconvincingly caught up in the scramble for the session tape, yet still receives a little mentoring from the legend.

Davis was famously reticent to play his celebrated standards, preferring to focus on his ever-evolving taste for freeform jazz (or “social music,” as he preferred), bebop, fusion, etc. “If the music don’t move on, it’s dead music,” he says.

In trying to embrace his subject’s ingenuity, Cheadle errs too much on the side of fancifulness to the detriment of coherence. That doesn’t degrade the power of his performance. Sometimes the solo outshines the tune.