Punk the Capital

This carefully curated documentary of the D.C. punk rock scene shows a movement that was less about spit-flecked rejection of society than simply pushing the musical edge wherever they could find it.

“That’s what punk rock really is, it’s music that’s not a product.”

I don’t now if I agree with this quote — plenty of punk rock was a product, a rebellion that like most successful rebellions results in the movement getting amalgamated into the mainstream rather than the other way around. But as shown in the historical documentary “Rock the Capital,” in the case of the punk movement in Washington D.C. in the late 1970s and early ’80s, it was more of a community than a major musical watershed.

Even if you’re not a punk aficionado — I’m not, though I like plenty of it — you’d be hard-pressed to name a lot of notable bands, songs or personalities that came out of the D.C. scene. It’s doubtful many people have heard of The Slickee Boys, Untouchables, The Enzymes, Bad Brains, Teen Idles or even Minor Threat, probably the biggest name in the bunch.

Henry Rollins of Black Flag and the RollinsBand came out of this scene and appears in the documentary to express his appreciation, though he left pretty early on and didn’t appear to look back.

It seems like rock ‘n’ roll documentaries seem to fall into one of two camps these days: nostalgic look-backs at big-name acts, or wistful remembrances of bands that didn’t last long or never broke out into pop culture consciousness. “The Sparks Brothers” is a recent example of the latter, and “Punk the Capital” follows the same route, though it’s about the scene rather than one group.

Directed by Paul Bishow and James June Schneider, it’s a carefully curated look at a thriving night scene in a place known for rolling up the streets at 6 p.m. when all the federal government workers went home to the suburbs. In this take, D.C. punk was less about spit-flecked rejection of society than simply pushing the musical edge wherever they could find it.

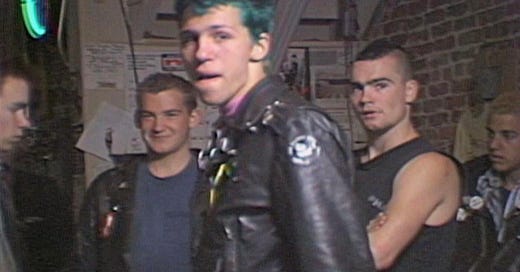

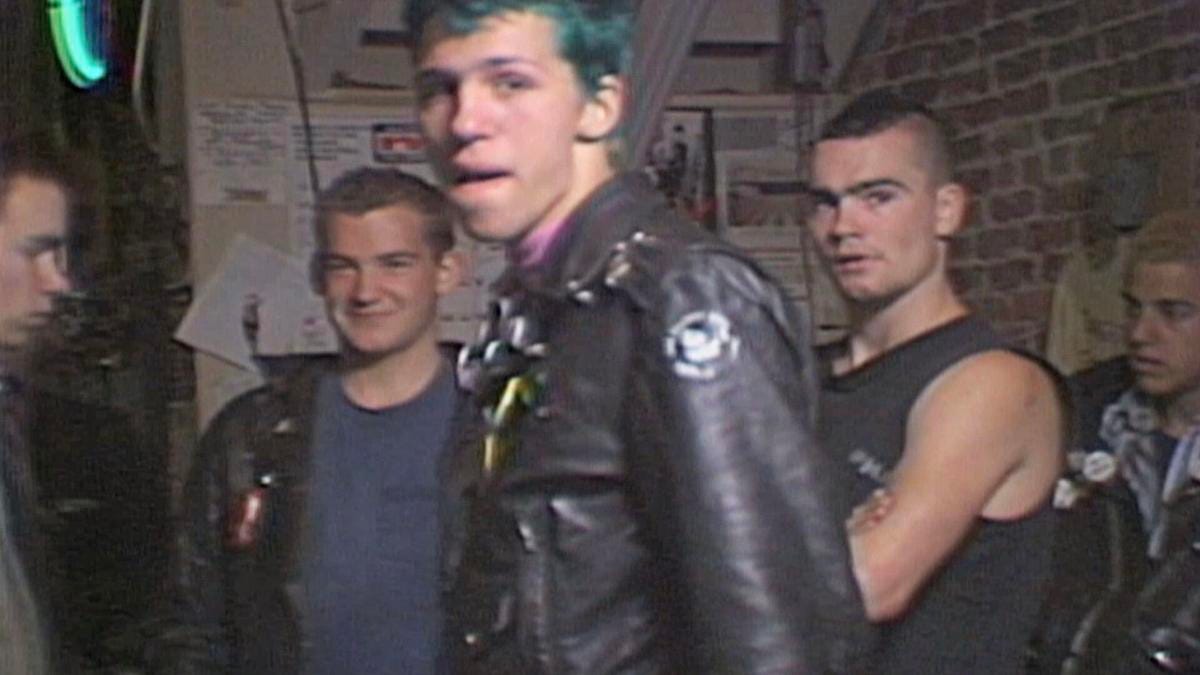

So the scene consisted of preppie children of government workers, Black social activists, blue-collar teens, geeks in glasses, and everything in between. It boasted a few women, though it was certainly a testosterone-fueled crowd, bringing slamdancing from the coasts to D.C. along with a few of the nastier tinges of punk.

We get a nice spread of musical tastes in the 90-minute runtime, with all kinds of sounds and colors, though the one unifying element is speed — these guys played lightning fast. Someone notes that the Beatles played 12 songs in just over an hour at their first U.S. concert at the Washington Coliseum. Minor Threat’s set of a dozen songs might last 13 minutes.

These bands, someone says, “make The Ramones seem like they’re asleep.”

The D.C. punk scene was notable for waves of rising and falling, becoming very popular and then nearly dying out entirely. Tiny record shops like Yesterday and Today barely kept the sound afloat. Around 1979 it was rescued by more or less taking over a women’s art collective called Madams Organ (after the Morgan Adams neighborhood in which the building sat), with some bands even living there for a time.

It was a performance venue, meeting place, residence and hangout all in one. Admission was rarely charged, and when a local record label was started to support them, Dischord, bands were shocked when they eventually started to receive checks in the mail.

I can’t say as I dug all of the music in “Punk the Capital,” but the energy of the crowds and bands is infectious. Performances often became participatory in which audiences members would crash the stage, or a singer might hand the microphone over to someone in the crowd to sing a few lines.

Newer bands came on the scene, doing something new or different that would shock even the bands started a couple years earlier. I was amused by the group Half Japanese, all bespectacled nerds, who seem barely acquainted with their instruments. But they’re clearly having a helluva time.

By the middle of the 1980s the punk movement had become something of a joke in pop culture, like the mohawked jerk blasting his boombox who gets sleeper-pinched by Spock in “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home.” That’s how a lot of people saw punk: angry young men spitting at society, and inviting disdain in return. Later, tinges of white supremacy would become associated with skinhead haircuts and loud, angry music.

This lively doc shows a multi-varied music scene that embraced anger but wasn’t animated by it — it simply was another emotion to tap for energy. One of the Big Brains members, Daryl Jenifer, talks of all things how they were motivated by the concept of PMA — positive mental energy. They saw their music as a way to strive, accomplish anything they wanted and change the world.

One song by Minor Threat, “Straight Edge,” even kicked off a mini-movement within the punk world that stressed abstinence (or at least moderation) of booze, drugs and promiscuous sex. How delightfully weird to have a genre where adherents are dismissed as “punks” embracing the power of the individual mind over societal muck.

I can’t say that watching “Punk the D.C.” made me want to rush out and buy this music. (In part because you often can’t, since much of it was never professionally recorded.) But even if you don’t appreciate the hyper, clashing sounds, you can’t help but respect the bravura youth who found humanistic harmony in what others heard as cacophony.