Reeling Backward: "Big Fish" (2003)

Tim Burton's lone outstanding, heartfelt film of the last two decades may not seem like a natural fit with his horror-tinged oeuvre. But in some ways it's his most intimate, personal movie.

This review is part of our free offerings to subscribers and visitors. Please consider supporting Film Yap through a paid signup to our Substack to receive all our premium content, now at a huge discount!

As regular readers of this space know, I soured on Tim Burton about 20 years ago. After years of being one of my favorite filmmakers, constantly seeking out quirky and original fare, he was (imho) lured by the gilded gold of easy Hollywood remakes or adaptations of moldy intellectual properties.

He traded in his inimitable spark for guaranteed box office grosses. His last feature, the utterly dreadful "Dumbo," represented a new nadir.

Really, over the last two decades I've only had a fondness for "Corpse Bride" and "Big Eyes," and the only thing Burton has made that I truly adored was "Big Fish." It has recently been re-released in a handsome Blu-ray/4K edition and is well worth revisiting.

In some ways the 2003 movie seems not to fit with Burton's oeuvre, with its predilection for combining horror, alienation and whimsy. But in other ways it's one of his most personal films, a Southern Gothic tale about an adult son trying to connect with the father he feels like he never really knew.

Burton lost both of his parents shortly before agreeing to the project, which originally had been slated for Steven Spielberg. Similarly, screenwriter John August encountered the novel by Daniel Wallace shortly after the death if his own father.

It seems at first glance like a childlike fable, what with its inclusion of giants, werewolves, witches and and magic.

But dig a little deeper and it's really aligned more with adults trying to reconcile their version of who their parents are with how they saw them as children -- with their own fears about parenthood and aging mixed in to the gumbo.

I don't think I've seen it since it first came out, and was surprised during my recent visit by how little Albert Finney is in it as the elderly Edward Bloom compared to Ewan McGregor as his younger self. My memory had them at about 50/50 screen time.

There's also a lot more of Billy Crudup than I recalled as his adult son, Will, about to become a father himself with his French wife, Josephine (possibly the first occasion I saw Marion Cotillard, though she didn't make a big impression at the time). Finney is essentially just used as the framing device for the flashbacks that form the bulk of the movie.

Edward is a boy from the fictional Ashton, Ala., who comes from nothing but is certain he is destined for a life of significance. Even if he doesn't enjoy one, he will invent it using the patchwork of mythical tall tales he likes to spin about himself.

The most famous is that on the day Will was born, literally shooting out of his mother's womb and scooting down the hospital hallway like a greased turkey shot from a cannon, Edward caught an enormous beast of a catfish using his wedding ring as bait, because the fish used to be a robber who could not resist the lure of gold.

The double entendre of the title is evident, as Edward is the quintessential big fish from a little pond, using his stories to charm, boast and teach all at once.

Will grew up idolizing his father, because he was a "sociable person" who was well-liked by everyone he met. But as a kid he actually believed all those stories and became disillusioned to grow older and find out they are (mostly) untrue. In the story Will is a reporter working for United Press International in France and is summoned back to Alabama by his father's illness.

(As is tradition, cinematic depictions of journalists come in only two flavors: hard-charging do-gooders who get into all sorts of danger and routinely sleep with their sources, or bored pedants dully talking on the phone while working approximately 15 hours a week. Will is the latter.)

The film does not actually cover any of Will's childhood, instead focusing on Edward's continuing adventures as a traveling salesman of various widgets and doohickeys, tearing around in a cherry red 1966 Dodge Charger. So Burton and August leave the growth of Will's animosity to our imagination.

Ostensibly it would seem like the screenplay needs a scene of a teen Will having it out with his dad, though emotionally I do not register its absence. Things are quickly established in an early scene at Will's wedding where Edward spins his big fish story to a rapt crowd, adding in the filigree of needing a a gold ring to catch the right woman.

A disgusted Will gets up and leaves his own reception, and we sense that jealousy and resentment form as much of the basis of the rift as anything. Will is introverted and authentic, no doubt choosing his vocation for its slavish devotion to the (often dull) truth.

Speaking as someone who shares those qualities, I can authoritatively say that we secretly admire the bullshitters like Edward who effortless command the center of attention.

So Will launches his own investigation into the truth behind his dad's stories, and without giving too much away finds that every one of them has a bedrock of truth in them, even if it's only a few grains. And parts of one story frequently blow into another, so the tales grow and cross-pollinate over the years.

For example, the story about his boyhood encounter with a witch (Burton muse/paramour Helena Bonham Carter) whose magic glass eye reveals the manner of your death gets linked in with a teenage Edward's arrival in the town of Spectre, where an 8-year-old girl pined for him. It's represented as a bucolic utopia with no roads and where the townsfolk all go barefoot in the green grass.

But it's also something of a trap, where people trade in their talents and ambition for the security of an ideal life of comfort and peace of mind.

Such is the case with Norther Winslow (Steve Buscemi), the most famous poet to come out of Edward's hometown, who is much admired in Spectre but finds his writing ability winnowed to borderline illiterate scribblings. After Edward leaves -- unheard of before then -- Norther later follows his footsteps and becomes a bank robber, first with a gun and then as a high financier in a suit.

Other amusing tales from Edward's past we get are his befriending a fearsome giant (Matthew McGrory) and his indentured servitude for three years at a circus, with the secretly hirsute ringmaster (Danny DeVito) dropping one clue per month to the identity of the woman he fell in love with at first sight. And there's his wartime infiltration of a North Korean stage show where he befriends conjoined twins (Ada Tai) and has a series of (unseen) adventures with them while returning to Alabama, where he was presumed dead.

Alison Lohman and Jessica Lange share screen time as Sandra, Edward's lady love. Both are a luminous presence, though rather severely underwritten. Sandra seems to have no inner life other than as the object of affection for Edward. I suppose this fits the form of the fable, Sandra representing an ideal more than a flesh-and-blood person, though seen today it accentuates the Y-chromosome-heavy nature of the piece.

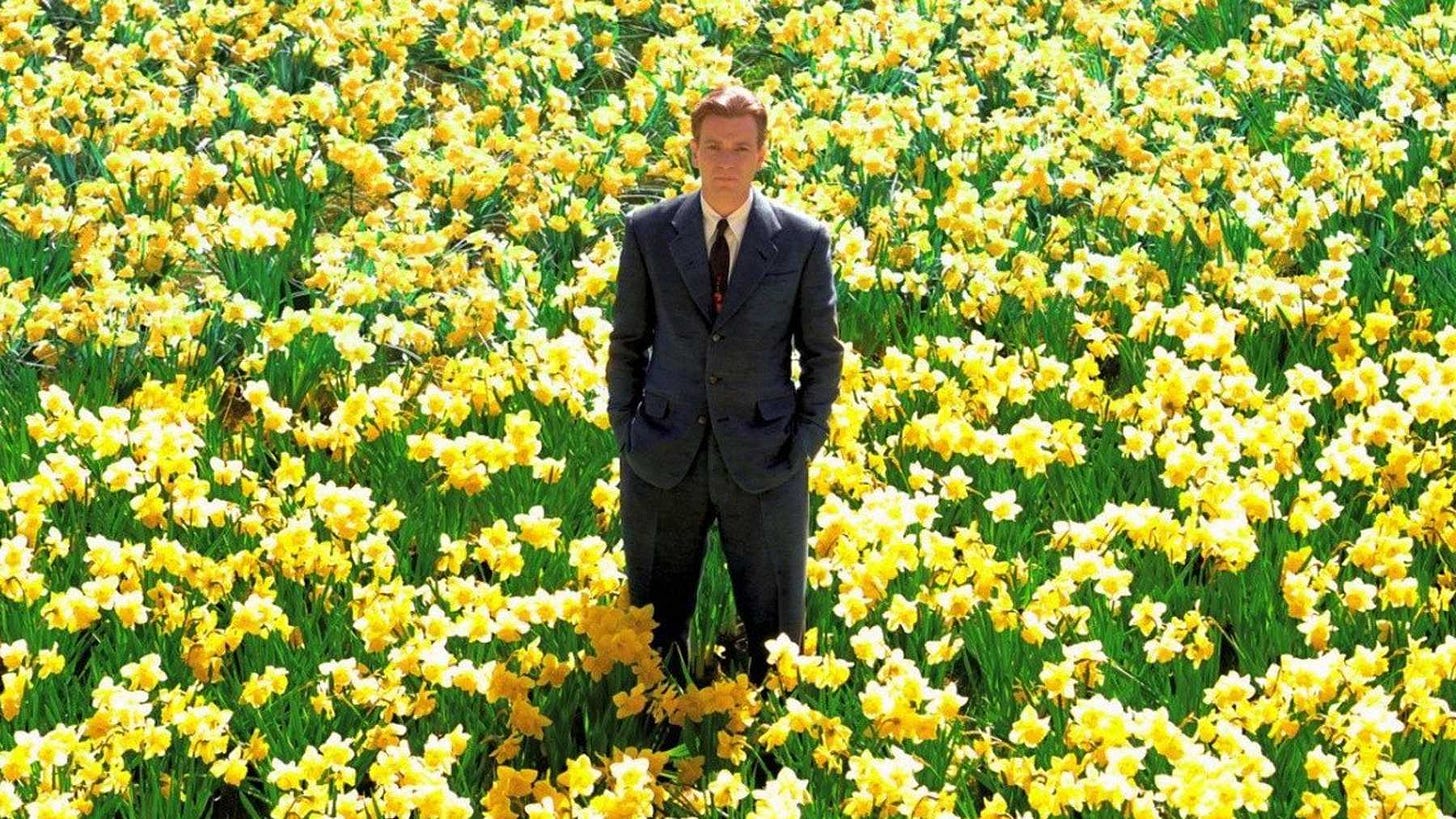

For a Tim Burton film, "Big Fish" is notable for its vibrant visuals and intense, even joyful use of color. (Cinematography by Philippe Rousselot, who worked with Burton on a three-film stretch over four years.)

One of its most iconic images is of Edward standing in a field of daffodils he has planted in front of Sandra's sorority house at Auburn University to attract her attention, wearing a bright blue suit as well. Another is the juxtaposition of young Edward on the road with Karl the giant, the already startling height differential of almost two feet between the actors accentuated by forced perspective camera work.

And also the idyllic oasis of Spectre, which seems of bigger importance in the story than I realized before. Like most things conjured from Edward's mouth it is fake -- though perhaps not completely so.

I have no idea if Burton consciously saw Spectre as a parable about his own choices as an artist, though in retrospect it is a clangingly obvious association. The Willy Wonkas and planets of apes are the lulling safety of hollow success, while his earlier, edgier stuff like "Ed Wood" represents the brambly woods through which we must traipse to find our truest, best selves.

Was Burton trying to tell us something about a desire to return to his outsider roots? If so, it seems clear which path he eventually chose. "Big Fish" failed to earn back its budget in domestic ticket sales, and "Corpse Bride" and "Big Eyes" were also not commercial successes.

Or perhaps it's us, the audience, who are responsible for Burton's banal wanderings as much as the director. We turn out for his populist dreck ($350 million for "Dumbo") and devalue truly audacious filmmaking like "Big Fish."

'Make something worthy and people will come' is the big lie we tell ourselves.