Reeling Backward: Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979)

Joan Micklin Silver's third directorial feature has become a cult classic for its anxious, authentic depiction of romance that is more complicated than the storybooks.

“Chilly Scenes of Winter” is pretty much the polar opposite of a romantic comedy, but that’s how the studio tried to sell it to the American public.

Joan Micklin Silver’s third feature film was released in 1979 marketed under the title of “Head Over Heels,” over her objection and that of her cast, who signed a petition against it. It bombed, playing in just New York and Los Angeles for short runs. Eventually it was re-released in 1982 under its original title, and fared a little better.

Interestingly, the original version features an incongruous happy ending in which the estranged couple gets back together, which tracks with the source material, the novel by Ann Beattie. The re-release (which I saw) leaves it on a more ambiguous note, and the distinct impression their hot-and-cold romance is finally dead for good.

It’s become something of a cult classic in the years since with occasional theatrical exhibitions. It’s currently not available for streaming — officially, though I found what I think is an unauthorized transfer on YouTube. It is available on Blu-ray on Amazon and a spiffier version from the Criterion Collection.

It stars John Heard, one of the ensemble cast in Micklin’s previous movie, the excellent “Between the Lines,” a depiction of former hippies fighting and loving while working at an alt-weekly newspaper. “Chilly” takes the same sort of Baby Boomers a few more years down the line, now yuppies in their 30s struggling to find love and stability.

I’ve been making it something of a project to catch up with the rest of Micklin’s eccentric filmography, and had this one next on my list at the recommendation of friend and colleague Lou Harry. Alas, I’ll confess I was a little let down by “Chilly Scenes,” though I still enjoyed it enough to recommend.

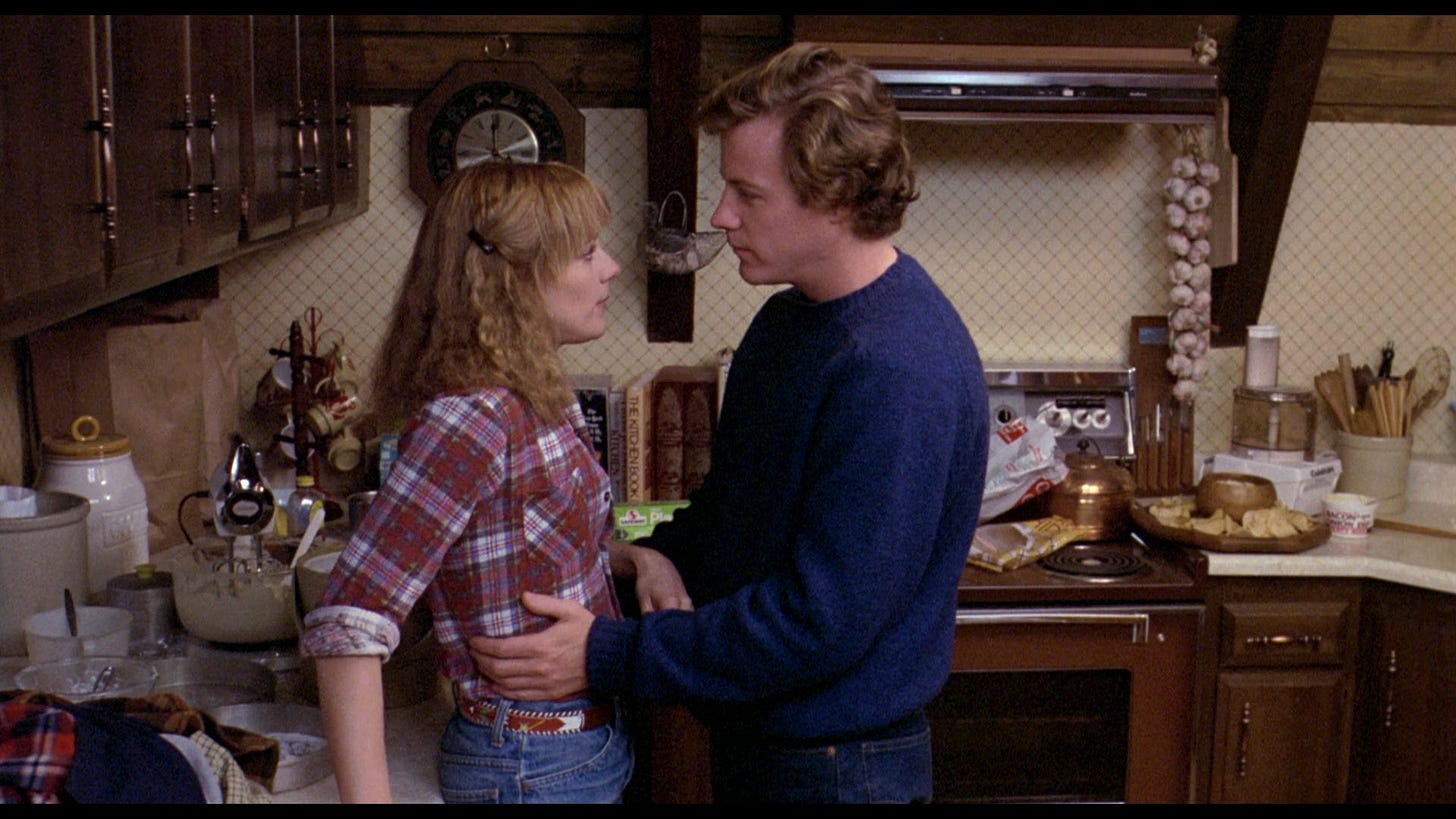

I give it props for its anxious, authentic depiction of romance that is more complicated than in the storybooks. Micklin adapted the book herself, and went for a deliberately messy but evocative narrative set a year after Charles (Heard) split up with Laura (Mary Beth Hurt) and still pines for her, with interlocking flashbacks to their time together.

My main disconnect was the depiction of Charles. When we first meet him he’s a mixed-up but likable guy, a civil servant in Salt Lake City whose job, by his own admission, involves writing reports he doesn’t care about for people who will never read them. Nonetheless he’s been promoted twice and now has an office and a little prestige.

“Whataya have?” he’s asked by the blind guy at the candy counter in the lobby of his office, where he buys a sweet snack upon leaving work each day. “I don’t have Laura,” he thinks to himself, his reverie prompting the counterman to ask the question again more urgently, suspecting he’s being ripped off. It becomes a running joke/encounter throughout the picture, which his internal answer changing each time.

Charles comes off as a miserable sap, unable to get over the two-month affair with Laura that ended nearly a year earlier. He met her while she was working in “the vault,” the archival center of his unnamed agency, hit on her and even jokingly invited her to move in with him. She actually did this soon after, and almost immediately Charles becomes cloying and creepy, accusing Laura of seeing somebody else or not being into him as much as he is her.

As it turns out, he’s not all wrong.

Laura is still married but separated from her husband, Jim (Mark Metcalf ), a former football player turned real estate agent specializing in the A-frame modernistic houses that were all the rage in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. He has his own daughter from a previous marriage, and Laura admits she has stuck around more for her attachment to the kid than the father.

Frequently during her time with Charles, she laments that she made a mistake by “leaving a good man for no reason.” He protests that she was justified because she has a right to be happy — and then sets about to make her just as unhappy himself.

It seemed to me that some of the superficial aspects of their onscreen coupling borrowed heavily from Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” — the anxiety-ridden man-child trying to tame the free-spirited gal with her own hill of troubles. Even Laura’s vaguely asexual outfits seem like a Utah version of Annie’s eclectic fashion sense.

As indicated by the title, both the contemporary story and the flashback take place during the interminable mountain zone winter, with snow and slush an omnipresent challenge, almost like a character unto itself than a background setting.

Charles tools around in his maroon 1966 Plymouth Valiant, the doors getting stuck with ice and him grumbling about its gas-guzzling in the post-oil crisis reconfiguration of American automotive. He owns his own house, a big handsome affair he inherited from his grandmother. Despite this and his relative professional success, he often frets about money.

Laura wound up leaving Charles to reunite with her husband, relegating him to creepy/pathetic activities like parking outside her house or her stepdaughter’s school so he can watch her. He does reach out by phone and is pleasantly surprised when she agrees to see him. Laura clearly still has feelings for Charles, but is obviously on some deeper journey where she’s eventually going to have detach herself from both of these men to experience any personal growth.

“Why would you choose someone who loves you too little over someone who loves you too much?” Charles demands at one point, possibly his lowest.

During his nastiest, Charles threatens to beat up Jim and then beat up Laura. When she announces she’s leaving him, he coldly warns her, “I’ll rape you.” We get the sense Charles is the beta-iest of beta males and would never actually put hands on a woman — or anyone — but just the threats alone are horrific emotional violence.

I immediately found myself estranged from Charles and his turmoil, and had difficulty reconnecting with him the rest of the way.

If the movie were just Charles and Laura and their bedraggled courtship playing out its string, I think it would get quite bogged down, even at just a 92 minute running time. Fortunately, Micklin sprinkles all sorts of interesting side characters and scenarios into the mix — quirky filigree that lightens the mood around the tense affair.

Peter Riegert plays Sam, Charles’ acerbic best friend since childhood, who has lost has job as a coat salesman and seems not very bothered by it. He moves in with Charles and starts sponging off him, not in a malicious way but with the certain understanding that whatever happens in each other’s lives, they will not back out on their pal. Sam mostly hangs around, drinking and watching sports, and trying to convince Charles he should let go of his fixation on Laura.

At one point the subject of Woodstock comes up. “We didn’t go to Woodstock,” Charles points out. “But we could have,” is Sam’s retort. Charles’ sister, Susan (Tarah Nutter), breaks the spell by insisting Woodstock was just a bunch of people walking around in the mud looking for a place to pee. It’s a funny but also revealing reflection on Boomers’ self-awareness of their own mythology.

Later, Susan will move out, hooking up with a young doctor played by Griffin Dunne in one of his earliest film roles.

At work Charles is seen as the fun boss by the pool of secretaries, playfully pinching the cheek of an older woman and sticking a pencil through the afro of a Black woman. They smile, but I can only imagine how such behavior would be received today — an automatic visit from HR, at the least.

Charles’ boss — Jerry Hardin, who made a career playing ineffectual authority figures, and is still with us at 94 — seeks his advice as a comparatively young and cool guy about his teenage son’s lack of success with women. Charles buys a Janis Joplin album and advises the boss to have his kid play it for the co-eds at his college.

There’s an ongoing interaction with Betty, an office frump played by Nora Heflin. Charles strings her along with some unserious flirtation, asking her help in coming up with a menu for a dinner party he never plans to hold, which becomes her hobby horse. She was also casually friends with Laura, and late in the movie when he finds out through Betty that Laura has walked out on her husband again, he dismisses her rather cruelly.

Charles’ mother, Clara, played by the great Gloria Grahame, is a faded beauty who takes to dressing up in lavish gowns and then climbing into the bath crying, calling Charles and telling him she’s going to commit suicide. Charles and his sister treat her as an overly dramatic pill, dutifully going over to pull her from her current snit. Their father died of a heart attack when he was 39, but only now she’s falling to pieces.

“You know what I think? I think one day she decided to go nuts because it's just easier that way,” Charles observes.

Clara remarried to Pete (Kenneth McMillan, forever Dune’s real Baron Harkonnen), a blowsy businessman who seems to truly adore her and sees her wild mood swings as the price of admission. He and Charles have a touchy relationship, not quite antagonism but very far from hospitable. One of the film’s lovely grace notes is the slow and slight, but real, rapprochement between them, bonding over Turtle Wax and dance lessons.

In addition to its strange release, “Chilly Scenes” had an odd beginning. The rights to Beattie’s book were actually purchased by a group of actors that included Metcalf and Dunne, who nonetheless only gave themselves bit parts in the movie. Mickler pitched herself to write and direct and they took her up on it.

United Artists wanted someone else besides Heard in the lead role — they offered to double the budget to $5 million if Treat Williams, Robin Williams or John Ritter replaced him — but Mickler and her actor/producers turned them down. Meryl Streep was up for the role of Laura at one point, and Jamie Lee Curtis auditioned for it.

I have a certain fondness for “Chilly Scenes of Winter,” if not ardent admiration. It’s a complicated film about complicated people who sometimes do things that make us like them not very much, if only for awhile. It’s perhaps too much like real life to be an outstanding movie.