Reeling Backward: Putney Swope (1969)

Robert Downey Sr.'s absurdist social satire about a Black man radicalizing an ad agency seems almost tame nowadays, but was considered quite off-the-wall and daring in its time.

Many people aren’t even aware that there was a Robert Downey Sr., apart from the obvious fact one must have existed to sire actor Robert Downey Jr., and that he was an active actor and filmmaker himself.

Downey (I’ll drop the appellation henceforth for brevity) made a lot of low-budget counterculture films during the 1960s and ‘70s, stuff most people haven’t even heard of but which influenced other filmmakers including Paul Thomas Anderson. His son actually had his film debut in 1970’s “Pound.”

Probably his best-known feature is “Putney Swope,” a 1969 satire that takes aim at pop culture and in particular television and advertising. It’s easy to see the traces of works like “Network” and “Mad Men” in its DNA. It also reminds me a lot of Andy Warhol’s darkly mirthful films of the time.

We get a strong sense of the film’s absurdist flavor in the opening minutes, where a helicopter delivers to the top of a New York City skyscraper an old man dressed like one of the “Easy Rider” bikers holding a briefcase. He is escorted before the executives of the powerful Elias advertising agency, introduced as a famous scientist, and asked to deliver his expert opinion on Harvey’s Beer, a languishing product in their client portfolio.

He declares that while ostensibly a refreshing beverage, people actually embrace beer because of its masculine connotations, which he summarizes as “A glass of beer is pee-pee dicky.” The man walks out, rewarded with a $28,000 paycheck for his trouble — and the top exec in the room assures the rest it was a bargain.

The premise of the story is that Elias himself soon arrives and falls dead on the table while trying to stutter out some new directive on advertising. After casually stripping the body of its watch, wallet and other valuables, the jealous executives must elect a successor — Elias Jr. (Allen Garfield) being told he’s too much of a nitwit for the job.

Since they cannot vote for themselves, the majority wind up casting their ballots for the titular character, who happens to be the only Black executive, thinking no one else will vote for him and give each of them a better chance at winning.

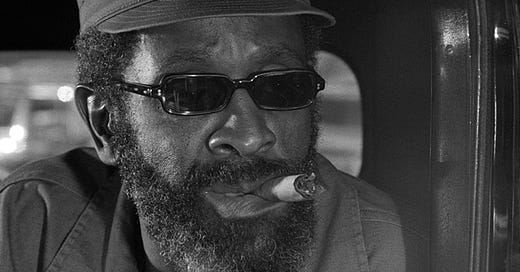

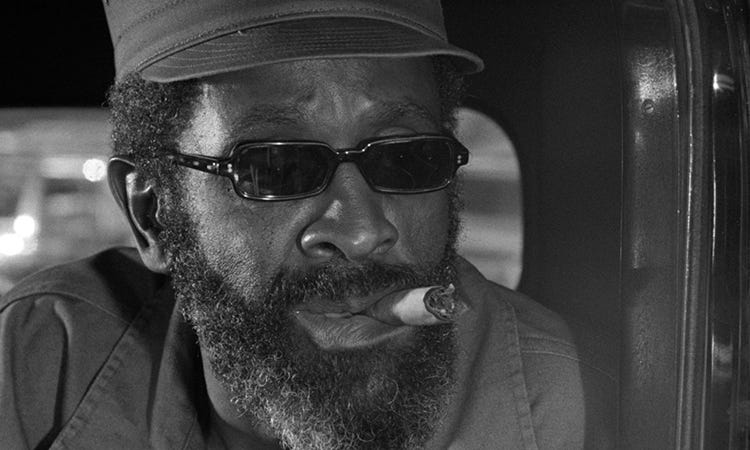

Taciturn and gravely-voiced, Swope (Arnold Johnson) assures the others he’s not going to make big changes. Then he fires all of them (but one, briefly, before he too is jettisoned), changes the moniker of the company to Truth and Soul, Inc. and brings in a regiment of Black Panther-ish radicals to run the show.

“I'm not gonna rock the boat. Rocking the boat’s a drag. What you do is sink the boat!” he declares.

Swope declares that the firm will become an organ for radical change, particularly in the country’s race relations, and his next order is banning any ads for “cigarettes, war toys or alcoholic beverages.” All of their clients immediately cancel their accounts, but soon come running back when Truth and Soul’s bracingly honest ads result in skyrocketing sales.

Example: a camera looms in on an average Black man eating dinner with his family, and when told of the product’s attributes he loudly exclaims, “No shit!”

There is also an ad for Lucky Airlines in which one fortunate ticket holder is allowed to romp in a special cushioned compartment with jumping stewardesses clothed (barely) in transparent chemises, their assets jiggling fetchingly in slo-motion.

The idea is that consumers are so used to being inundated with BS and flimflam that they’ll respond enthusiastically to a bawdy but honest take. It reminds me of the sort of “fake ad” humor we would go on to see on “Saturday Night Live,” “Robocop,” etc.

The story, such as it is, operates as a series of vignettes loosely held together. Swope demands his new and returning clients present him with $1 million in cash apiece upfront, and the bags of loot are taken to a room where they are bounced off a basketball backboard into a glass receptable for storage, presumably to fund the coming revolution.

Swope has various recurring hangers-on and yes-men and -women, though he is quick to fire anyone who disagrees with him or displeases him. Among them is an inept bodyguard (Buddy Butler), a largely wordless man in white suit and sunglasses who appears to be his #2 (Vincent Hamill), a mouthy lady with amorous tastes (uncredited — in fact, no women in the cast are) and an obsequious young blond exec who is told he gets paid less because he doesn’t think about the implications of giving him a raise.

He’s basically a token white.

There’s also a figure referred to as the Arab (I’m not sure if he’s the actor credited as Hawker, Joker or Mr. Cards) who wears a kufiya and sunglasses and talks openly about undermining Swope and even sleeping with his wife. For some reason Swope tolerates this man bemusedly — apart from dubbing him “Lawrence of Nigeria” — though when it’s time to split up the loot he makes a point of excluding him.

The President of the United States turns up, played by a Little Person named Mimeo (also uncredited), who has an incredibly high-pitched childish voice and is always accompanied by his similarly statured wife. He keeps pushing Swope to do an ad for the automobile company Borman Six, since he is a stockholder himself. This president keeps a bunch of lackeys around, similar to Swope, though in his case mostly to butter him up and keep up a steady patter of deadpan jokes to amuse him and the missus.

There’s also a high-profile photographer named Mark Focus (more uncrediting) who shows up from time to pitch his portfolio, whom Swope dubs the best photog in the business, and then huffily refuses to hire him.

I can see why audiences might have reacted negatively to the notion of a bunch of Black radicals pushing white people around and making lewd TV commercials. There’s even a pimple ad with a handsome young mixed couple who canoodle onscreen. Downey largely plays the race relations for laughs rather than social commentary, just another segment of society due for a sendup.

While the movie is shot in black-and-white, all the commercials play in vivid colorized sequences. The idea being, I suppose, that in the modern age nothing seems more real than high-dollar fakery.

This was Johnson’s first acting role — he would go on to be in “Shaft” and “Menace II Society” — and reportedly couldn’t remember his lines during shooting. He mostly just walks around and stares sullenly, delivering his brief glottal pronouncements.

Downey actually dubbed out all of Johnson’s dialogue and replaced it with his own voice, something he claims he always planned to do. Perhaps it was his ultimate undercutting of his own character, having a radical Black man voiced by a white. I’m sure nowadays this would be regarded as “problematic.”

Although Swope is treated by his underlings as a messianic figure, he’s just another flawed individual who winds up being corrupted by the system. His employees begin to learn this later in the movie, accusing him of “confusing obscenity for originality,” and a revolt seems in the offing.

But they soon change their tune when offered raises and promotions, and even agree to start doing ads for the three forbidden vices — though Swope later claims this was a test. He takes a bagful of the money for himself and departs, content to let the young’uns take the revolution wherever their whims carry them. Though this results in the rest of the stash getting burned up by the discontented Arab.

“Putney Swope” was seen as quite radical in its day. Its poster, showing an upraised hand flipping the bird, with the offending digit replaced by a comely young woman, was refused for advertising in most every newspaper in the country. Roger Ebert objected when his own Chicago Sun-Times did so.

It had a limited theatrical run and is regarded now as purely a cult film, though the pinnacle of Downey’s oeuvre.

Its message isn’t quite as blistering today, nor does its copious use of nudity and the f-word hold the same level of shock. But it’s the nature of every successful revolution to one day become the establishment. “Swope” stands as a monument to a rapidly shifting 1960s society and an agreeably puckish sense of humor we can hope never goes out of style.