Reeling Backward: The Broadway Melody (1929)

Though derided by some as a hopelessly outdated relic, the first musical Oscar winner for Best Picture remains a surprisingly gritty and daring romantic triangle story.

“The Broadway Melody” was just the second Best Picture winner at the Oscars, and was also the first “talkie” and first musical to do so. Musicals were very popular as prestige filmmaking for a long time, winning eight more best picture statuettes between 1937 and 1969, and then a long hiatus before “Chicago” won the most recent 20 years ago.

(“La La Land” came close, but…)

“Broadway” was a huge hit and spawned a number of films that weren’t so much sequels as extensions of the franchise with chronological suffixes: “Broadway Melody of…” 1936, 1938 and 1940, respectively. Another planned for 1944 was scuttled. And the original was remade under a different title in 1940.

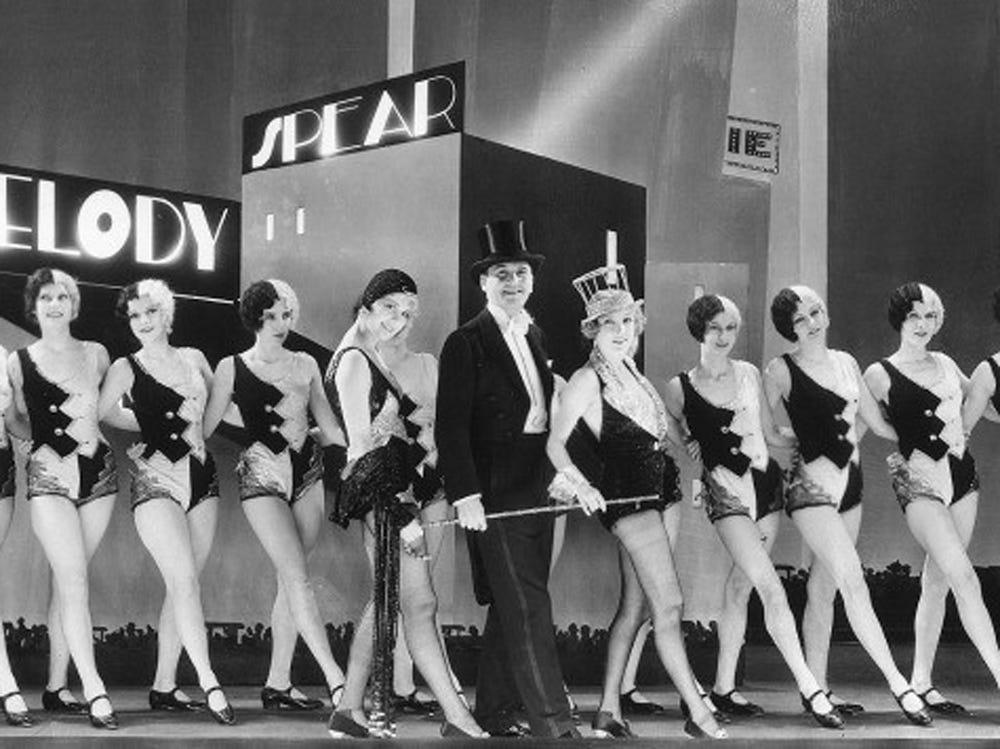

It’s very much in the grand tradition of “Puttin’ on a show,” in which the characters are performers in a movie or stage production that forms the backdrop of the story. Musical scenes take place both as interludes driving the character arcs and as part of the show-within-a-show.

“Singin’ in the Rain” employed this same technique, and even borrowed the title song and “You Were Meant for Me” by Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown. George M. Cohan’s classic “Give My Regards to Broadway,” already 25 years old when “Melody” came out, is another standout used in the opening number.

“Rain” is for me the best musical ever and one of my favorite films of all time, though it didn’t fare nearly as well at the Academy Awards, earning (and losing) just two nominations.

Interestingly, Best Picture was the only Oscar “The Broadway Melody” won. This was not exceptional in the early days of the Academy Awards, as “Grand Hotel” (1932) and “Mutiny on the Bounty” (1935) join it as single-winners, and six other films have won just two (“Spotlight” most recently).

In a weird quirk we can probably attribute to startup pains, no nominees were officially announced that year beforehand, though star Bessie Love and director Harry Beaumont were subsequently listed as having gotten nods.

The reputation of “Melody” has not fared well with the passing of years, with many modern observers calling it a hopelessly outdated relic of its time. It currently holds an abysmal 39% rating on Rotten Tomatoes (though that may change a bit after I link this essay).

There were many technical challenges in the early days of talking pictures reflected in this movie, such as microphone positioning and intrusive background noise. (“Singin’ in the Rain” mocked them, and indeed I wouldn’t be surprised if “Melody” was a primary inspiration.)

There are a number of scenes where the sound falls out entirely, so we have eerily silent moments within a sound picture. In dialogue scenes, it’s not unusual for the characters to huddle together ridiculously close, their noses just a couple of inches away, as they no doubt struggle to share the same mike.

“Melody” also contained a colorized sequence, something that had been done even during the silent era through painstaking hand-painting of celluloid frame-by-frame. Alas, this scene has been lost to time.

Going in with such low expectations, I was surprised how much I admired “Melody.” Yes, it’s not very technically polished and the societal mores reflected are archaic. But what do you expect, people? It’s 94 years old!!

At the center is a gritty romantic triangle, as song-and-dance siblings the Mahoney Sisters come to New York and struggle to get their big break. Love plays Harriet aka “Hank,” the older and bossier sister who runs the show. Anita Page is Queenie, the younger blonde, not as talented but gorgeous enough to make all the men act silly around her.

Hank is engaged to Eddie Kearns (Charles King), a vaudeville performer and songwriter who’s already established on Broadway and is starring in the next big musical from super-producer Zanfield (Eddie Kane), a figure who’s no doubt a stand-in for Ziegfeld and his follies. Eddie promises to get them parts in the show.

A rival (Mary Doran) sabotages their audition by dropping a box inside the piano, though they manage to eke out small supporting parts when Zanfield is entranced by Queenie’s beauty. Even those bit roles are later cut, and Queenie is relegated to sexual object with a non-speaking part in little clothing.

Eddie finds himself falling for Queenie, and she returns his affections, though neither wants to betray Hank. To distract attention, Queenie allows herself to be romanced by Jock Warriner, a notorious wealthy cad played by Kenneth Thomson.

Hank and Eddie try desperately to talk her out of the affair — Hank because she knows he just wants her for sex and Eddie out of jealousy — but Queenie insists on her independence, and it seems like the trio will go their separate ways.

(Side note: most resources refer to Warriner’s character as Jacques, but everyone in the movie uses a hard “j” in pronouncing his name, and he even signs a note as “Jock” — so that’s what I’m going with.)

I was surprised how lascivious the movie is, with Love and Page shown disrobing in their first scene, and women cavorting about in various states of undress backstage. Even Eddie gets a scene in his underwear. There are also several obviously gay male supporting characters, in the usual mincing stereotypes of the day. Jock’s aggressive overtures stop just short of rape.

Remember, the Hays Code strictly censoring film content was not instituted until 1934, and before then movies were considerably more daring than after. “Wings,” the first Best Picture, featured lesbians and nude men.

It was the Jazz Age, after all…

Despite its transitional production values and outdated gender roles, “The Broadway Melody” remains a surprisingly effective and entertaining piece of filmmaking that is a proud entry in the pantheon of Best Pictures.