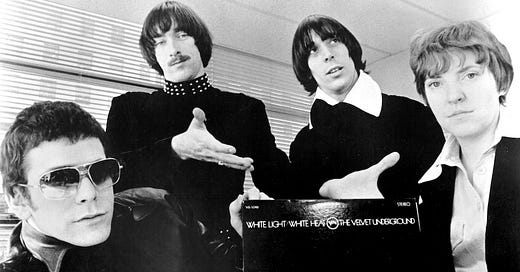

The Velvet Underground

Todd Haynes' thoroughly unconventional documentary looks at the rise, evolution and dissolution of one of rock 'n' roll's most eclectic groups.

Like what you’re seeing? Please consider supporting Film Yap with a modest subscription, now at a huge discount!

Rock documentaries follow a certain, oft predictable pattern: “So-and-so grew up in nowhere, hated his parents and his town, started a band to meet girls, struggled for a minute and then hit it big, and now we’ll have 30 talking heads telling you about how consequential they were to musicians who came after.”

Todd Haynes’ “The Velvet Underground” doesn’t do that. It eschews expansive biographies of the experimental rock foursome’s members and instead focuses on their motivations as individual artists, and how they meshed and evolved upon coming together. It instructs us why a band that never had a hit single is still worth making a feature-length documentary about.

It also traces the gradual dissolution of the band, acknowledging that the seeds of its destruction were planted alongside the same innovative fruit the band bore. A group like The Velvet Underground was not destined for a decades-long run. Indeed, two of the members wound up as a medieval history professor and computer programmer, respectively.

I admit I had scant familiarity with TVU prior to this documentary. I knew they were a niche darkling band in the 1960s, Lou Reed was the disaffected frontman before launching his solo career… and that’s about it. Couldn’t have cited a song or a sound to represent them in my inner pop culture Rolodex.

I found it fascinating that pop art godfather Andy Warhol was their “manager” their first few years — though I’m not sure this is the proper term. They were playing a few dive gigs and Warhol enlisted them to be the “house band” for The Factory, his art studio/hangout/HQ where the talented and the beautiful flocked, hoping to get noticed and become a star.

The relationship was always a strained one, with Warhol seeming more intent on incorporating the band into his iconoclast art movement rather than pushing them as far as they could go as a distinct musical endeavor.

Warhol paired the band with German singer Nico for their first album, a strange forced collaboration between this dour quartet dressed all in black and a woman with limited vocal ability but whose blonde ice princess image captivated the times. Still, some of their songs have an undeniable haunting appeal even today.

Warhol concocted elaborate light and dance shows for their gigs, playing movies over them while playing onstage, turning performances into a true multimedia performance art experience.

Indeed, a lot of the footage in the doc came from Warhol’s own cinematic noodlings, including long staring profiles of the band members while we hear them talk. Reed is dead, of course, along with guitarist Sterling Morrison, though we hear from the in various interviews and recordings.

Founder John Cale and drummer Maureen “Moe” Tucker are still with us, and sit for extensive interviews. Cale talks insightfully about the formation of their sound, which really was more of an artistic ethos that took pieces from classical, rock, R&B and experimental music from people like La Monte Young — long, sustained tones that built upon natural harmonics — to find something unique.

I don’t know how to describe The Velvet Underground songs, hearing much of it for the first time while watching this movie. Certainly they did not conform to anything like pop culture standards of the mid-60’s. They boasted a lot of unearthly, ethereal sounds and lyrics that focused on things like drug use, depression, negative body image, etc.

Even an inexpert like me can hear and see the roots laid down for later movements that sprung up like the punk rock of the 1970’s or ‘90s grunge.

Cale is an interesting figure who talks without regret about being pushed out of the band by Reed, who felt their ability to collaborate was at an end. He’s a true boundary-pusher, someone who embraces improvisation and experimentation onstage, always looking for the next new thing.

Tucker is more grounded and has better insights on the relationships that drove and fractured the group — not to mention being caustically funny. I LOL’d at her description of a disastrous tour swing through California, talking about how they hated hippies and all that free love BS.

(Though I wish the documentary narrative would’ve focused a little more on her journey, a pretty rare unicorn as a girl drummer in a downbeat boy-band when there weren’t a lot of either.)

We also hear from various other figures connected to the band: Warhol filmmaker Jonas Mekas, friend Allan Hyman, Reed’s sister Merrill, actress/film critic Amy Taubin, Tony Conrad, superfan/musician Jonathan Richman and Cale replacement Doug Yule (through vintage recordings; he’s alive but didn’t participate in the film).

Haynes employs some of Warhol’s own light-play techniques in this documentary, with lots of flashing lights, fast-moving snippets of archival footage and multiple screens. The resulting experience is gorgeous but a little bit hazy and dreamlike, like a pleasant high that starts to spiral into darker places.

In other words, it matches the aura of The Velvet Undeground just so.